The Hadoop Distributed File System: Architecture and Design

Introduction

The Hadoop File System (HDFS) is as a distributed file system running on commodity hardware. It has many similarities with existing distributed file systems. However, the differences from other distributed file systems are significant. HDFS is highly fault-tolerant and can be deployed on low-cost hardware. HDFS provides high throughput access to application data and is suitable for applications that have large datasets. HDFS relaxes a few POSIX requirements to enable streaming access to file system data. HDFS was originally built as infrastructure for the open source web crawler Apache Nutch project. HDFS is part of the Hadoop Project, which is part of the Lucene Apache Project. The Project URL is here.

Assumptions and Goals

Hardware Failure

Hardware Failure is the norm rather than the exception. The entire HDFS file system may consist of hundreds or thousands of server machines that stores pieces of file system data. The fact that there are a huge number of components and that each component has a non-trivial probability of failure means that some component of HDFS is always non-functional. Therefore, detection of faults and automatically recovering quickly from those faults are core architectural goals of HDFS.

Streaming Data Access

Applications that run on HDFS need streaming access to their data sets. They are not general purpose applications that typically run on a general purpose file system. HDFS is designed more for batch processing rather than interactive use by users. The emphasis is on throughput of data access rather than latency of data access. POSIX imposes many hard requirements that are not needed for applications that are targeted for HDFS. POSIX semantics in a few key areas have been traded off to further enhance data throughout rates.

Large Data Sets

Applications that run on HDFS have large data sets. This means that a typical file in HDFS is gigabytes to terabytes in size. Thus, HDFS is tuned to support large files. It should provide high aggregate data bandwidth and should scale to hundreds of nodes in a single cluster. It should support tens of millions of files in a single cluster.

Simple Coherency Model

Most HDFS applications need write-once-read-many access model for files. A file once created, written and closed need not be changed. This assumption simplifies data coherency issues and enables high throughout data access. A Map-Reduce application or a Web-Crawler application fits perfectly with this model. There is a plan to support appending-writes to a file in future.

Moving computation is cheaper than moving data

A computation requested by an application is most optimal if the computation can be done near where the data is located. This is especially true when the size of the data set is huge. This eliminates network congestion and increase overall throughput of the system. The assumption is that it is often better to migrate the computation closer to where the data is located rather than moving the data to where the application is running. HDFS provides interfaces for applications to move themselves closer to where the data is located.

Portability across Heterogeneous Hardware and Software Platforms

HDFS should be designed in such a way that it is easily portable from one platform to another. This facilitates widespread adoption of HDFS as a platform of choice for a large set of applications.

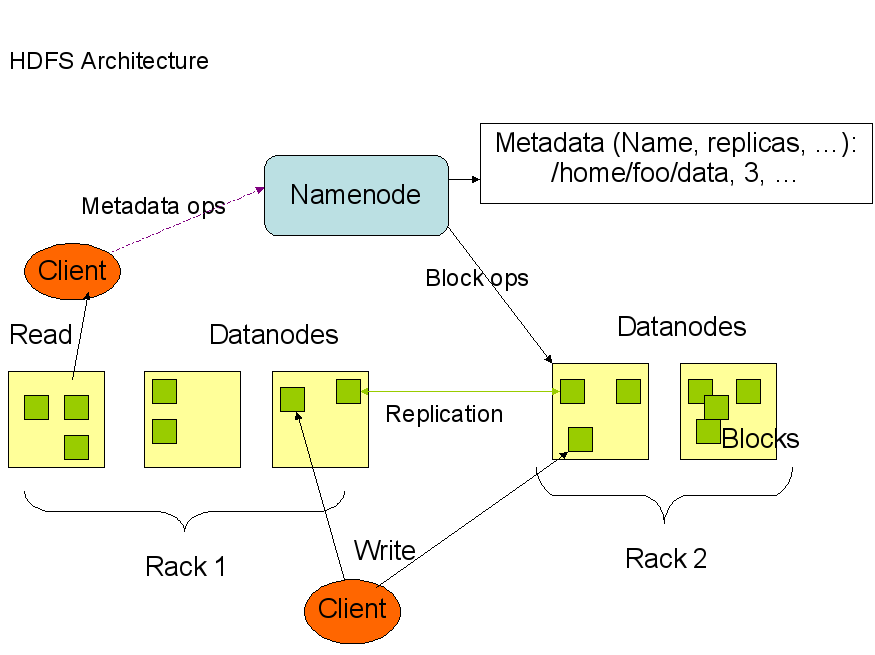

Namenode and Datanode

HDFS has a master/slave architecture. An HDFS cluster consists of a single Namenode, a master server that manages the filesystem namespace and regulates access to files by clients. In addition, there are a number of Datanodes, one per node in the cluster, which manage storage attached to the nodes that they run on. HDFS exposes a file system namespace and allows user data to be stored in files. Internally, a file is split into one or more blocks and these blocks are stored in a set of Datanodes. The Namenode makes filesystem namespace operations like opening, closing, renaming etc. of files and directories. It also determines the mapping of blocks to Datanodes. The Datanodes are responsible for serving read and write requests from filesystem clients. The Datanodes also perform block creation, deletion, and replication upon instruction from the Namenode.

The Namenode and Datanode are pieces of software that run on commodity machines. These machines are typically commodity Linux machines. HDFS is built using the Java language; any machine that support Java can run the Namenode or the Datanode. Usage of the highly portable Java language means that HDFS can be deployed on a wide range of machines. A typical deployment could have a dedicated machine that runs only the Namenode software. Each of the other machines in the cluster runs one instance of the Datanode software. The architecture does not preclude running multiple Datanodes on the same machine but in a real-deployment that is never the case.

The existence of a single Namenode in a cluster greatly simplifies the architecture of the system. The Namenode is the arbitrator and repository for all HDFS metadata. The system is designed in such a way that user data never flows through the Namenode.

The File System Namespace

HDFS supports a traditional hierarchical file organization. A user or an application can create directories and store files inside these directories. The file system namespace hierarchy is similar to most other existing file systems. One can create and remove files, move a file from one directory to another, or rename a file. HDFS does not yet implement user quotas and access permissions. HDFS does not support hard links and soft links. However, the HDFS architecture does not preclude implementing these features at a later time.

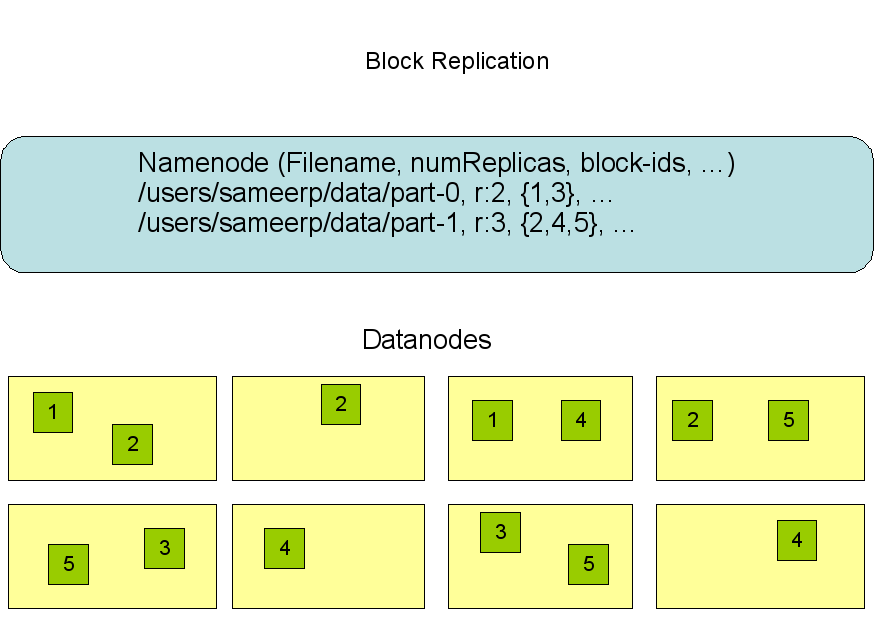

The Namenode maintains the file system namespace. Any change to the file system namespace and properties are recorded by the Namenode. An application can specify the number of replicas of a file that should be maintained by HDFS. The number of copies of a file is called the replication factor of that file. This information is stored by the Namenode.

Data Replication

HDFS is designed to reliably store very large files across machines in a large cluster. It stores each file as a sequence of blocks; all blocks in a file except the last block are the same size. Blocks belonging to a file are replicated for fault tolerance. The block size and replication factor are configurable per file. Files in HDFS are write-once and have strictly one writer at any time. An application can specify the number of replicas of a file. The replication factor can be specified at file creation time and can be changed later.

The Namenode makes all decisions regarding replication of blocks. It periodically receives Heartbeat and a Blockreport from each of the Datanodes in the cluster. A receipt of a heartbeat implies that the Datanode is in good health and is serving data as desired. A Blockreport contains a list of all blocks on that Datanode.

Replica Placement . The First Baby Steps

The selection of placement of replicas is critical to HDFS reliability and performance. This feature distinguishes HDFS from most other distributed file systems. This is a feature that needs lots of tuning and experience. The purpose of a rack-aware replica placement is to improve data reliability, availability, and network bandwidth utilization. The current implementation for the replica placement policy is a first effort in this direction. The short-term goals of implementing this policy are to validate it on production systems, learn more about its behavior and build a foundation to test and research more sophisticated policies in the future.

HDFS runs on a cluster of computers that spread across many racks. Communication between two nodes on different racks has to go through switches. In most cases, network bandwidth between two machines in the same rack is greater than network bandwidth between two machines on different racks.

At startup time, each Datanode determines the rack it belongs to and notifies the Namenode of the rack id upon registration. HDFS provides APIs to facilitate pluggable modules that can be used to determine the rack identity of a machine. A simple but non-optimal policy is to place replicas across racks. This prevents losing data when an entire rack fails and allows use of bandwidth from multiple racks when reading data. This policy evenly distributes replicas in the cluster and thus makes it easy to balance load on component failure. However, this policy increases the cost of writes because a write needs to transfer blocks to multiple racks.

For the most common case when the replica factor is three, HDFS.s placement policy is to place one replica on the local node, place another replica on a different node at the local rack, and place the last replica on different node at a different rack. This policy cuts the inter-rack write traffic and improves write performance. The chance of rack failure is far less than that of node failure; this policy does not impact data reliability and availability guarantees. But it reduces the aggregate network bandwidth when reading data since a block is placed in only two unique racks rather than three. The replicas of a file do not evenly distribute across the racks. One third of replicas are on one node, two thirds of the replicas are on one rack; the other one third of replicas is evenly distributed across all the remaining racks. This policy improves write performance while not impacting data reliability or read performance.

The implementation of the above policy is work-in-progress.

Replica Selection

HDFS tries to satisfy a read request from a replica that is closest to the reader. If there exists a replica on the same rack as the reader node, then that replica is preferred to satisfy the read request. If a HDFS cluster spans multiple data centers, then a replica that is resident in the local data center is preferred over remote replicas.

SafeMode

On startup, the Namenode enters a special state called Safemode. Replication of data blocks does not occur when the Namenode is in Safemode state. The Namenode receives Heartbeat and Blockreport from the Datanodes. A Blockreport contains the list of data blocks that a Datanode reports to the Namenode. Each block has a specified minimum number of replicas. A block is considered safely-replicated when the minimum number of replicas of that data block has checked in with the Namenode. When a configurable percentage of safely-replicated data blocks checks in with the Namenode (plus an additional 30 seconds), the Namenode exits the Safemode state. It then determines the list of data blocks (if any) that have fewer than the specified number of replicas. The Namenode then replicates these blocks to other Datanodes.

The Persistence of File System Metadata

The HDFS namespace is stored by the Namenode. The Namenode uses a transaction log called the EditLog to persistently record every change that occurs to file system metadata. For example, creating a new file in HDFS causes the Namenode to insert a record into the EditLog indicating this change. Similarly, changing the replication factor of a file causes a new record to be inserted into the EditLog. The Namenode uses a file in its local file system to store the Edit Log. The entire file system namespace, the mapping of blocks to files and filesystem properties are stored in a file called the FsImage. The FsImage is a file in the Namenode.s local file system too.

The Namenode has an image of the entire file system namespace and file Blockmap in memory. This metadata is designed to be compact, so that a 4GB memory on the Namenode machine is plenty to support a very large number of files and directories. When the Namenode starts up, it reads the FsImage and EditLog from disk, applies all the transactions from the EditLog into the in-memory representation of the FsImage and then flushes out this new metadata into a new FsImage on disk. It can then truncate the old EditLog because its transactions have been applied to the persistent FsImage. This process is called a checkpoint. In the current implementation, a checkpoint occurs when the Namenode starts up. Work is in progress to support periodic checkpointing in the near future.

The Datanode stores HDFS data into files in its local file system. The Datanode has no knowledge about HDFS files. It stores each block of HDFS data in a separate file in its local file system. The Datanode does not create all files in the same directory. Instead, it uses a heuristic to determine the optimal number of files per directory. It creates subdirectories appropriately. It is not optimal to create all local files in the same directory because the local file system might not be able to efficiently support a huge number of files in a single directory. When a Datanode starts up, it scans through its local file system, generates a list of all HDFS data blocks that correspond to each of these local files and sends this report to the Namenode. This report is called the Blockreport.

The Communication Protocol

All communication protocols are layered on top of the TCP/IP protocol. A client establishes a connection to a well-defined and configurable port on the Namenode machine. It talks the ClientProtocol with the Namenode. The Datanodes talk to the Namenode using the DatanodeProtocol. The details on these protocols will be explained later on. A Remote Procedure Call (RPC) abstraction wraps the ClientProtocol and the DatanodeProtocol. By design, the Namenode never initiates an RPC. It responds to RPC requests issued by a Datanode or a client.

Robustness

The primary objective of HDFS is to store data reliably even in the presence of failures. The three types of common failures are Namenode failures, Datanode failures and network partitions.

Data Disk Failure, Heartbeats and Re-Replication

A Datanode sends a heartbeat message to the Namenode periodically. A network partition can cause a subset of Datanodes to lose connectivity with the Namenode. The Namenode detects this condition be a lack of heartbeat message. The Namenode marks these Datanodes as dead and does not forward any new IO requests to these Datanodes. The data that was residing on those Datanodes are not available to HDFS any more. This may cause the replication factor of some blocks to fall below their specified value. The Namenode determines all the blocks that need to be replicated and starts replicating them to other Datanodes. The necessity for re-replication may arise due to many reasons: a Datanode becoming unavailable, a corrupt replica, a bad disk on the Datanode or an increase of the replication factor of a file.

Cluster Rebalancing

The HDFS architecture is compatible with data rebalancing schemes. It is possible that data may move automatically from one Datanode to another if the free space on a Datanode falls below a certain threshold. Also, a sudden high demand for a particular file can dynamically cause creation of additional replicas and rebalancing of other data in the cluster. These types of rebalancing schemes are not yet implemented.

Data Correctness

It is possible that a block of data fetched from a Datanode is corrupted. This corruption can occur because of faults in the storage device, a bad network or buggy software. The HDFS client implements checksum checking on the contents of a HDFS file. When a client creates a HDFS file, it computes a checksum of each block on the file and stores these checksums in a separate hidden file in the same HDFS namespace. When a client retrieves file contents it verifies that the data it received from a Datanode satisfies the checksum stored in the checksum file. If not, then the client can opt to retrieve that block from another Datanode that has a replica of that block.

Metadata Disk Failure

The FsImage and the EditLog are central data structures of HDFS. A corruption of these files can cause the entire cluster to be non-functional. For this reason, the Namenode can be configured to support multiple copies of the FsImage and EditLog. Any update to either the FsImage or EditLog causes each of the FsImages and EditLogs to get updated synchronously. This synchronous updating of multiple EditLog may degrade the rate of namespace transactions per second that a Namenode can support. But this degradation is acceptable because HDFS applications are very data intensive in nature; they are not metadata intensive. A Namenode, when it restarts, selects the latest consistent FsImage and EditLog to use.

The Namenode machine is a single point of failure for the HDFS cluster. If a Namenode machine fails, manual intervention is necessary. Currently, automatic restart and failover of the Namenode software to another machine is not supported.

Snapshots

Snapshots support storing a copy of data at a particular instant of time. One usage of the snapshot-feature may be to roll back a corrupted cluster to a previously known good point in time. HDFS current does not support snapshots but it will be supported it in future release.

Data Organization

Data Blocks

HDFS is designed to support large files. Applications that are compatible with HDFS are those that deal with large data sets. These applications write the data only once; they read the data one or more times and require that reads are satisfied at streaming speeds. HDFS supports write-once-read-many semantics on files. A typical block size used by HDFS is 64 MB. Thus, a HDFS file is chopped up into 128MB chunks, and each chunk could reside in different Datanodes.

Staging

A client-request to create a file does not reach the Namenode immediately. In fact, the HDFS client caches the file data into a temporary local file. An application-write is transparently redirected to this temporary local file. When the local file accumulates data worth over a HDFS block size, the client contacts the Namenode. The Namenode inserts the file name into the file system hierarchy and allocates a data block for it. The Namenode responds to the client request with the identity of the Datanode(s) and the destination data block. The client flushes the block of data from the local temporary file to the specified Datanode. When a file is closed, the remaining un-flushed data in the temporary local file is transferred to the Datanode. The client then instructs the Namenode that the file is closed. At this point, the Namenode commits the file creation operation into a persistent store. If the Namenode dies before the file is closed, the file is lost.

The above approach has been adopted after careful consideration of target applications that run on HDFS. Applications need streaming writes to files. If a client writes to a remote file directly without any client side buffering, the network speed and the congestion in the network impacts throughput considerably. This approach is not without precedence either. Earlier distributed file system, e.g. AFS have used client side caching to improve performance. A POSIX requirement has been relaxed to achieve higher performance of data uploads.

Pipelining

When a client is writing data to a HDFS file, its data is first written to a local file as explained above. Suppose the HDFS file has a replication factor of three. When the local file accumulates a block of user data, the client retrieves a list of Datanodes from the Namenode. This list represents the Datanodes that will host a replica of that block. The client then flushes the data block to the first Datanode. The first Datanode starts receiving the data in small portions (4 KB), writes each portion to its local repository and transfers that portion to the second Datanode in the list. The second Datanode, in turn, starts receiving each portion of the data block, writes that portion to its repository and then flushes that portion to the third Datanode. The third Datanode writes the data to its local repository. A Datanode could be receiving data from the previous one in the pipeline and at the same time it could be forwarding data to the next one in the pipeline. Thus, the data is pipelined from one Datanode to the next.

Accessibility

HDFS can be accessed by application by many different ways. Natively, HDFS provides a Java API for applications to use. A C language wrapper for this Java API is available. A HTTP browser can also be used to browse the file in HDFS. Work is in progress to expose a HDFS content repository through the WebDAV Protocol.

DFSShell

HDFS allows user data to be organized in the form of files and directories. It provides an interface called DFSShell that lets a user interact with the data in HDFS. The syntax of this command set is similar to other shells (e.g. bash, csh) that users are already familiar with. Here are some sample commands:

Create a directory named /foodir : hadoop dfs -mkdir /foodir

View a file /foodir/myfile.txt : hadoop dfs -cat /foodir/myfile.txt

Delete a file /foodir/myfile.txt : hadoop dfs -rm /foodir myfile.txt

The command syntax for DFSShell is targeted for applications that need a scripting language to interact with the stored data.

DFSAdmin

The DFSAdmin command set is used for administering a dfs cluster. These are commands that are used only by a HDFS administrator. Here are some sample commands:

Put a cluster in Safe Mode : bin/hadoop dfsadmin -safemode enter

Generate a list of Datanodes : bin/hadoop dfsadmin -report

Decommission a Datanode : bin/hadoop dfsadmin -decommission datanodename

Browser Interface

A typical HDFS install configures a web-server to expose the HDFS namespace through a configurable port. This allows a Web browser to navigate the HDFS namespace and view contents of a HDFS file.

Space Reclamation

File Deletes and Undelete

When a file is deleted by a user or an application, it is not immediately removed from HDFS. HDFS renames it to a file in the /trash directory. The file can be restored quickly as long as it remains in /trash. A file remains in /trash for a configurable amount of time. After the expiry of its life in /trash, the Namenode deletes the file from the HDFS namespace. The deletion of the file causes the blocks associated with the file to be freed. There could be an appreciable time delay between the time a file is deleted by a user and the time of the corresponding increase in free space in HDFS.

A user can Undelete a file after deleting it as long as it remains in the /trash directory. If a user wants to undelete a file that he/she has deleted, he/she can navigate the /trash directory and retrieve the file. The /trash directory contains only the latest copy of the file that was deleted. The /trash directory is just like any other directory with one special feature: HDFS applies specified policies to automatically delete files from this directory. The current default policy is to delete files that are older than 6 hours. In future, this policy will be configurable through a well defined interface.

Decrease Replication Factor

When the replication factor of a file is reduced, the Namenode selects excess replicas that can be deleted. The next Heartbeat transfers this information to the Datanode. The Datanode then removes the corresponding blocks and the corresponding free space appears in the cluster. The point to note here is that there might be a time delay between the completion of the setReplication API and the appearance of free space in the cluster.

References

by Dhruba Borthakur